Obstetric Fistula and the Situation in Mozambique

Dr. Igor Vaz1

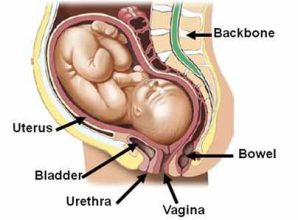

A vesico-vaginal fístula is an opening between the bladder and the vagina due to the destruction of tissue that has been compressed by the head of the foetus during childbirth.

Fistulas range from a small orifice through which women constantly lose urine to extensive destruction of the bladder, the vagina, the rectum, the perineum and sphincter, with vascular and neurological damage in the pelvic region. This leads to the constant loss of faeces and an inability to walk. Women can no longer become pregnant and it is impossible for them to live with their families and friends or even to have a relationship.

These complications arise where social, cultural, political and economic factors result in an inadequate care network and their greatest impact is on women in developing countries. Current levels of economic and social development in most African countries mean that there is little hope of finding a rapid solution and reducing the prevalence of fistulas through mother and child health care.

In addition to prolonged labour, other physical causes of this pathology include accidental surgical lesions related to pregnancy and invasive operations to bring about an abortion. Many of these causes occur both within the national health service (due to poor institutional coverage and the poor training of its technicians), and also outside the national health system, due to negative attitudes that are detrimental to assistance during childbirth and pregnancy. These factors are worse in the rural areas of developing countries, including Mozambique.

Studies in other countries with social, cultural, political and economic characteristics similar to those of Mozambique have found that about 70% of women with fistulas are under 30 years of age.

In some cases percentages cover the roughly 14-15 year old age group. Most women develop fistulas during their first pregnancy when they are very young, in cultures where a girl is pushed into marriage while still in the puberty phase and where “being a mother” is an indicator of the status of a married, adult woman. In other cases there is an unexpected pregnancy or marriage to escape from poverty.

They frequently lose the baby during childbirth, and some even end up dying from birth complications, while those who survive are physically and psychologically traumatised.

Accused by husbands of being responsible for the death of their children, after being rejected by their husbands they are socially stigmatised by their own families and by the community that has no appropriate mechanisms for supporting these women either physically by sending them to health facilities or through psychosocial assistance.

This means that in the absence of a response at all levels, these women face an enormous disability as their fistulas get worse. It is more than just a physical disability, affecting the function and structure of the organ. There are also psychological effects, contributing to psycho-social disorders such as less autonomous capacity, anxiety problems, depression, conjugal difficulties, inability to get pregnant again etc.

Weak access to health units is another risk factor for the deterioration of vesico-vaginal fistulas. The literature confirms this risk factor in various developing countries where most hospitals are in urban areas, a long way from rural areas where most fistulas occur. Without support, without money and without transport, experience has shown that it is only by chance that a minimal percentage of these women get to health units, frequently after the problem has been dragging on for an average of five years.

National context

The areas with high fistula rates in Mozambique are the provinces of Niassa, Tete, Zambézia, Nampula e Inhambane. The high prevalence of fistulas is linked to the low coverage of assistance during childbirth in the rural areas in these provinces, but also a higher incidence of cultural factors such as premature marriage, with childbirth at a very early age. In addition to institutional and cultural factors, weak socio-economic status and absolute poverty make the country highly vulnerable to a dramatic panorama of vesico-vaginal fistulas.

Treating fistulas requires a survey, information, trained personnel and the creation of surgical teams. At the moment these conditions only exist in centres that do routine work in this field: the Maputo Central Hospital, Beira Central Hospital, Nampula Central Hospital, Quelimane Provincial Hospital and Lichinga Provincial Hospital in Niassa.

The Ministry of Health, that has been receiving assistance from UNFPA since 2002, has a national programme on treatment and is training health technicians in preventing and treating vesico-vaginal fistulas. There have been training and treatment missions to high prevalence provinces.

Most fistulas can be treated through simple surgery that does not require sophisticated equipment or advanced technical surgical knowledge. The reason that most fistulas remain untreated is essentially because health personnel are unaware of the problem.

Given the high prevalence of other pathologies in the country, obstetric fistulas have not been considered a public health problem at the policy level. They have thus not been identified as a priority health problem in health units that are overloaded with other, more frequent pathologies. In addition, most patients do not have decision-making capacity that enables them to pressure the community (including their relatives) and health institutions and demand changes in attitude that defend their rights as people deserving attention by these institutions. As already mentioned, many of them are young illiterate women having their first child and they are unaware of the possibility of improving their quality of life through surgery. The community is also ignorant of both the causes of fistulas and the resources for treating them.

From a psycho-social perspective, these women find themselves facing stigma due to the complications of a pathology that the health system is unable to address, and also due to the physical disability it causes, preventing them from participating in community resources and activities. So they lose their identity as adult women able to produce and reproduce. It is clearly a problem that is closely related to the issue of discrimination against women and thus falls under gender policies on promoting the empowerment of Mozambican women.

For the few people who are able to be covered by the national health system, with three centres operating on fistulas in the country, most have to travel long distances to gain access to treatment and have to wait months, sometimes years, for an operation.

Unfortunately, surgery does not resolve all their problems. Some women continue with incurable lesions. After treatment, society and other ministries and organisations linked to women are responsible for their reintegration into communities. This reintegration does not mean just returning home, but also enabling these women to improve their education level and receive training in small crafts/trades so that they can be self-sufficient.

1. Urologist; Head of the Urology Department of Maputo’s Central Hospital

* * *

Information in English

Information in English